What do you call the network in your household or business?

Are there shrieks of ‘Muuuum is the Wi-Fi down?’ or perhaps partners asking ‘What’s going on with the broadband babe?’

Or if you’re the boss of a SME, maybe you’ve got employees interrupting your meetings asking why the internet is lagging.

What’s the most popular name for internet connections?

Broadband Internet Service Provider TalkTalk engaged Axicom to commission a new online survey of 2,000 UK adults, conducted by OnePoll. The survey claims to find that the most popular name for home internet connections is Wi-Fi.

A third of respondents said they describe their internet connection using the term Wi-Fi, with ‘broadband’ and ‘internet’ coming in second and third place respectively.

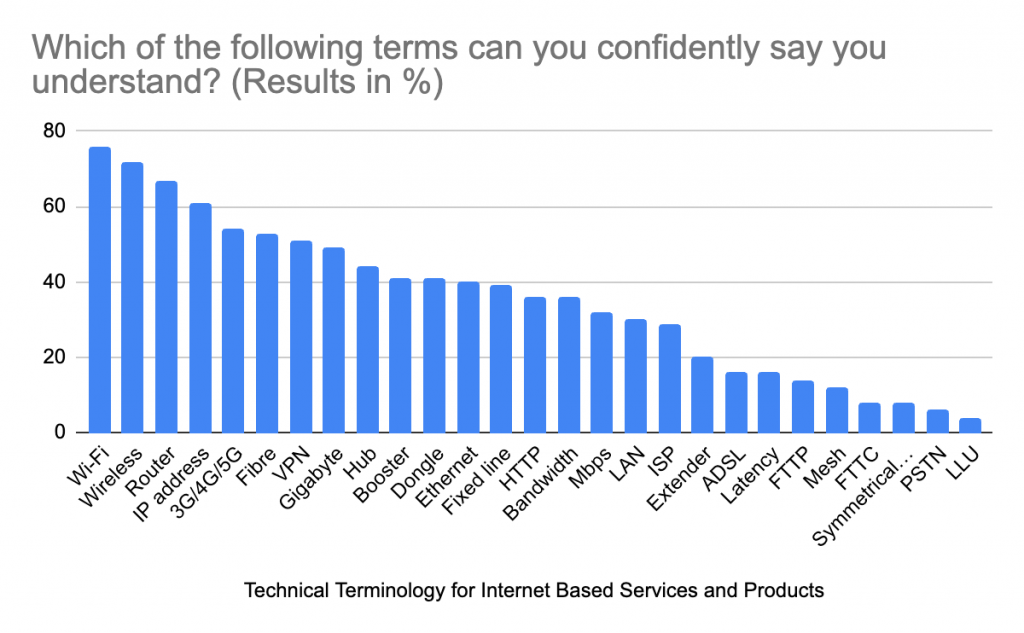

The survey also quizzed respondents on their understanding of different wireless technology terms, with 76% of those asked saying they ‘confidently understand’ the term Wi-Fi.

Less confidently understood was ‘fibre’ with only half of the respondents confident with their understanding of its meaning. Interestingly, ‘fibre’ is often a term flung around by telecoms companies to describe their broadband products and services, which begs the question – Do consumers actually understand what they are being sold?

Do Consumers Understand the Internet Products and Services Being Sold to Them?

The results to this particular survey would suggest the answer is unfortunately no, with 69% of respondents admitting that technology-related jargon is difficult to understand.

Perhaps then, the aim of this most recent online survey was to gather information on how ISP TalkTalk can market their products and internet services to potential customers – Both business and residential.

If consumers are not understanding terms like ‘fibre’ then perhaps the focus on the term ‘Wi-Fi’ instead will increase understanding and thus sales. It does seem to be the renewed focus of their recent brand refresh, despite the technical terminology not being entirely correct.

Does this therefore reinforce a misconception around the understanding of technical internet terminology, rather than provide an accurate explanation?

What is your understanding of some of the terms used in the survey? You can see a breakdown of the most understood terminology below, given in percentages.

There seems to be a healthy understanding of the terms Wi-Fi, Wireless, Router and IP Address. Those less understood were concepts like Latency, FTTP/FTTC, Mesh, PSTN and LLU.

What Do TalkTalk Have to Say?

The Product and Propositions Director for TalkTalk shared the companies thoughts on their recent survey and how the results are influencing how they talk to their customers in order to ensure the best understanding of their services and products.

“Wi-Fi is a staple in all our homes, yet as an industry we haven’t kept up with the times when we talk to our customers. At TalkTalk, we’re shifting to talk about Wi-Fi more and more, as it’s the connectivity – making sure streaming or browsing is seamless – that matters most for our millions of customers.

Our latest research tells us that people prefer to communicate in the same way that they speak, without jargon, and our industry should reflect that. We know we’re not perfect, and we have much to do, but this is the first step in delivering a Better Way to Wi-Fi for customers who just want transparency and information they can confidently understand. And this builds trust between us and our customers too.”

What Does Wi-Fi Mean to You?

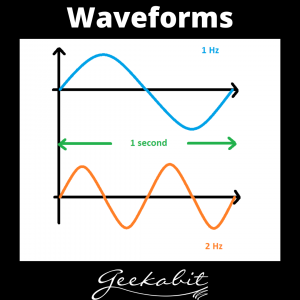

Whilst the term Wi-Fi might still feel like technical jargon to some, most homes and businesses use Wi-Fi to describe a WLAN, or Wireless Local Area Network connection that originates from a router that distributes the broadband internet connection from your Internet Service Provider.

Wi-Fi and Broadband are not the same thing, but consumers seem to be regularly using the term ‘Wi-Fi’ to loosely apply to their wireless internet connection as a whole.

When this starts to run into difficulties is when an issue arises. Someone shouts ‘The Wi-Fi’s gone down!’ – What’s the problem? It could be that the router is faulty and not transmitting a signal to user devices. In this instance, the actual broadband connection coming from outside the property could be completely fine – It’s only the transmission of the signal that has the issue.

Likewise, the router could be transmitting a signal to end users and their devices remain connected, but conference calls aren’t connecting. The problem isn’t the hardware, but the actual broadband connection coming from the ISP.

2 very different problems but both labelled as a ‘Wi-Fi’ problem.

Do You Get Lost in Technical Internet Jargon?

If you need reliable Wi-Fi for your business but find it hard to follow all the terminology, then don’t worry. Not everyone can be Wi-Fi Experts! Thankfully the wireless engineers here at Geekabit have all the knowledge and expertise needed to navigate your network and get you the best wireless connection for your premises.

Get in touch with our Hampshire, Cardiff or London based teams today to see how we can help.