Research commissioned by Three found that issues with poor connectivity were costing SME’s in Britain £18.77 billion per year.

Research found that small to medium sized businesses (including micro businesses) in the UK who give employees work phones are losing out on over 1 hour of work time per employee, per week. Poor connectivity leads to employees being unable to get online or complete their work effectively.

1 hour per week per employee may not sound like a big deal on the face of it, but for medium sized businesses, this equates to 250 hours of working time being lost every single week.

This loss of working time has a bigger impact on things than you may think. In partnership with YouGov and Development Economics, Three’s research found that:

- The British economy is significantly impacted by loss of business revenue. The amount of economic output lost is estimated to be £7.7bn per year.

- The cost of poor connectivity hits the professional and retail sectors the harders

- Businesses are already facing challenging times – almost 75% of SME’s are reducing costs

Which industries are hit hardest by poor connectivity?

Two of the largest sectors in the British economy were hit the hardest with poor connectivity – Retail, and Professional Services (including legal, accounting and media businesses).

How much revenue is lost in these sectors due to poor connectivity?

- Professional Services – Loss of £5.3 billion per year (annual output loss of £2.8bn to the economy)

- Retail – Loss of £3.7 billion per year (annual output loss of £560m to the economy)

Connectivity isn’t the only challenge for SME’s

SME’s aren’t just facing a challenge with poor connectivity – They’re also facing challenges with the cost of living crisis and talent shortages.

SME’s are also feeling the heat of rising costs, with 71% looking at where they need to reduce spending. 32% of SME’s are looking to cut costs on things like phone contracts, which they believe they are spending too much on.

29% of SME’s (and 48% of medium sized businesses) also worry about losing employees due to not having good technology, which is cause for concern when there is also a shortage of talent in the majority of industries.

Combine all of this with poor connectivity causing problems with work effectiveness and you can see why it’s causing a bit of a headache for small and medium sized businesses.

Do SME’s need more tech support?

In order to operate, grow and thrive in business, it is absolutely vital for SME’s to have a strong online connection.

36% of SME’s believe that better mobile phone connectivity would enable them to perform better. 1 in 5 SME’s are also concerned that their business could get left behind if they don’t know how to use the latest mobile phone technology.

Unfortunately, almost 50% of SME’s feel that the tech industry uses complex language that makes it difficult to understand the latest technology, creating a barrier for these businesses without proper support and knowledge.

What can be done to provide SME’s with tech and connectivity support?

It seems that many tech schemes and concepts are aimed at larger corporate structures, failing to meet the needs of SME’s in a more cost effective way. It’s so important for tech providers to recognise the needs of SME’s and tailor their services to meet them. SME’s need simple, straightforward tech offerings with a level of service that large corporates would expect.

For a business to be able to perform and for their employees to effectively do their jobs, it all comes down to connectivity.

For most businesses, connectivity is the core of it all – Poor connectivity is simply not an option. It’s imperative for SME’s to carefully consider the options available to them when it comes to connectivity, tech and mobile. They need a simple, cost effective option that leaves them in control.

The research outlined above just goes to show how poor connectivity can really hold a business back. Research from The Federation of Small Businesses found similar results which showed that 45% of small businesses experience unreliable voice connectivity (going up to 57% in rural areas).

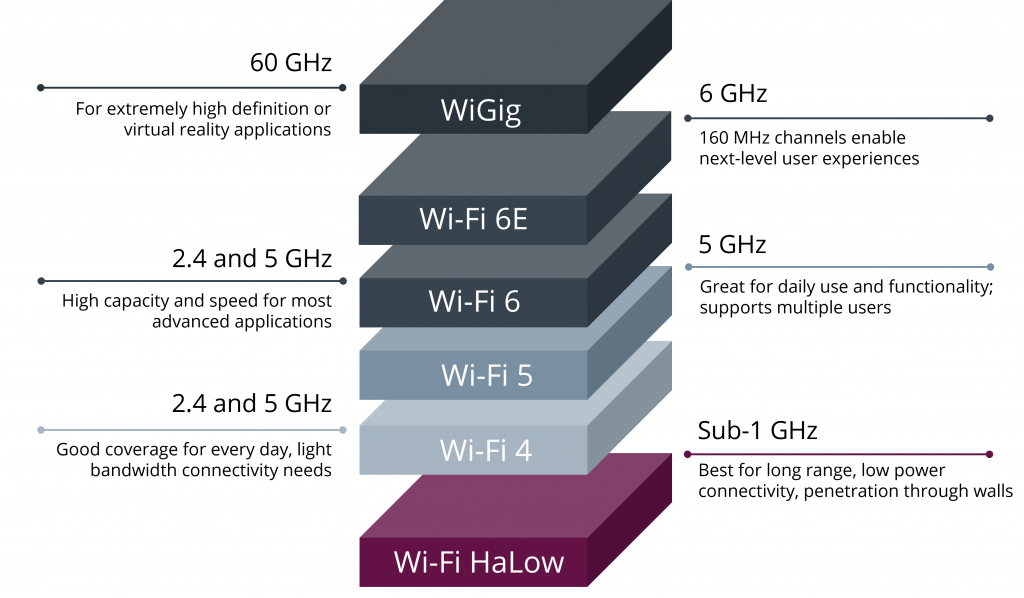

SME’s are a big part of the UK economy. To see growth and productivity, we need strong and reliable digital, mobile and vocal connectivity. That includes 4G and 5G accessibility for all.

Can Geekabit Help?

If you are a SME and are struggling with poor connectivity, then call in the experts. Our experienced Wi-Fi engineers can help at any stage of network deployment – From site surveys to design to installation.

We’re only a phone call away, and can help get your business properly connected.

Thinking you’re too rural? We’ve got 4G for that! Our mobile and satellite broadband options could be just the thing you’re looking for.

Get in touch with our Wi-Fi experts today.